Would a hall full of diverse Caribbean nationalities have the context to fully appreciate a production covering the life of a Trinbagonian Calypsonian, or would it fall on deaf ears? This was the question I pondered as I sat in anticipation of the Carifesta XV presentation of Canboulay Productions’ Ten To One at the Frank Collymore Hall in Barbados, on Sunday 24th August, 2025. That trepidation was short-lived.

From the first familiar chords of the Mighty Sparrow’s Slave which signaled the opening of the production, the auditorium reverberated with the voices of several audience members singing along with the cast, word for word, loudly, joyfully, defiantly. By the time the eponym Ten to One is Murder rolled around, the crowd was not just an audience but a choir, proof that calypso, though birthed in Trinidad, long ago became the Caribbean’s inheritance and the world’s treasure.

Staged in honor of The Mighty Sparrow’s 90th birthday, and as specially invited guests of Carifesta XV, Rawle Gibbons’ calypso drama reminded us that Sparrow’s music transcends geography, politics, and generations. His lyrics, sometimes biting, quite often bawdy, but always brilliant, carry the history of a people that resonated far beyond Port of Spain.

The play itself is the third instalment in Gibbons’ Calypso Trilogy, following Sing De Chorus and Ah Wanna Fall, and charts the meteoric rise of the Mighty Sparrow in Trinidad’s calypso scene from the mid 1950s into the late 1960s. Anchored in Port of Spain, Trinidad, the work evokes a city alive with political ferment, colonial tensions, and the stirring promise of independence. Sparrow is positioned alongside his contemporaries, Blakie, Kitchener, Melody, Christo, Chalkdust, Caruso, Superior, and Duke as essential voices in a shared cultural and political soundscape. Through lyric, movement and rhythm, the piece traces how the artform evolved from carnival entertainment into social commentary, political expression, and identity making for those who had long been marginalized.

The cast’s haunting rendition of the production’s opening number succeeded in setting a tone that was both ritualistic and resistant. In all my experiences in theatre to date, I never witnessed an audience singing along with a play with such abandon. This segued seamlessly into Dr. Eric Williams (portrayed by Anton Brewster) political address, explaining the significance of the phrase “Massa Day Done” to the crowd of onlookers, not as a forgotten slogan but as the lived reality of prostitutes, panmen, and “badjohns”.

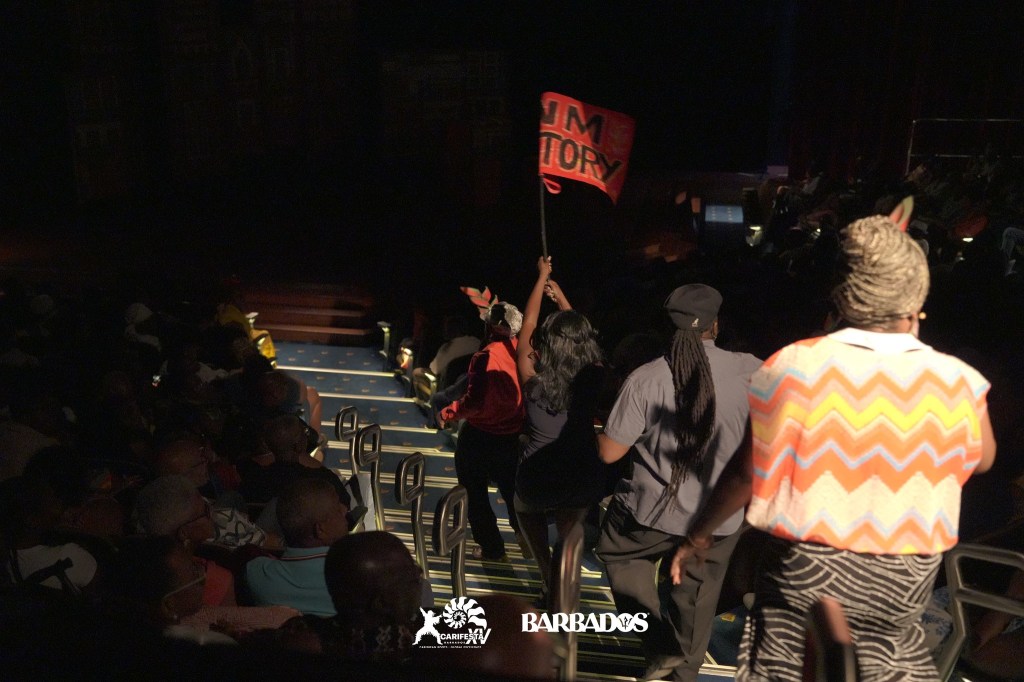

What made this introduction especially powerful was the refusal to keep the audience at a safe distance. Rather than entering from the wings, the cast flooded the theatre from the back of the hall, singing, chanting, and moving through the aisle. It was a bold choice by veteran Director Louis McWilliams which elevated otherwise simple staging into world building, where the spectator was immersed in a living, breathing environment where the social margins stepped into the centre. The line between performer and audience was blurred, and the audience willingly participated. Though this added to the play’s dynamism, it occasionally created moments of discomfort. In a later scene, the light came on to two characters positioned at the back of the hall, prompting patrons positioned in the front to twist in their seats until the action moved to the main stage. Nevertheless, the choice to break the fourth wall was largely successful. It foreshadowed Sparrow’s role as the people’s mouthpiece but also reminded us that calypso itself has always been participatory, thriving in call and response, in laughter and rebuttal, in the collective energy of community.

Henry Muttoo’s set design deepened this immersion with a subtle but evocative sense of place. The backdrop was composed of modest building facades, painted in layered tones of yellows and browns. At its centre, the Maple Leaf Club sign firmly situated the action on Charlotte Street, a site historically shared by calypsonians and steelpan players of the time. Stage left, Tantie’s Tea Shop provided a contrasting detail: a small communal hub where gossip and storytelling flowed as freely as tea, offering the audience an immediate sense of the social exchanges that shaped Sparrow’s world. The design was understated, likely influenced by the practical demands of moving the production from Trinidad to Barbados, but it was never lacking. Instead of overwhelming spectacle, the minimalism gave the performers room to command the stage, their voices and movements building Port of Spain more vividly than any elaborate set could.

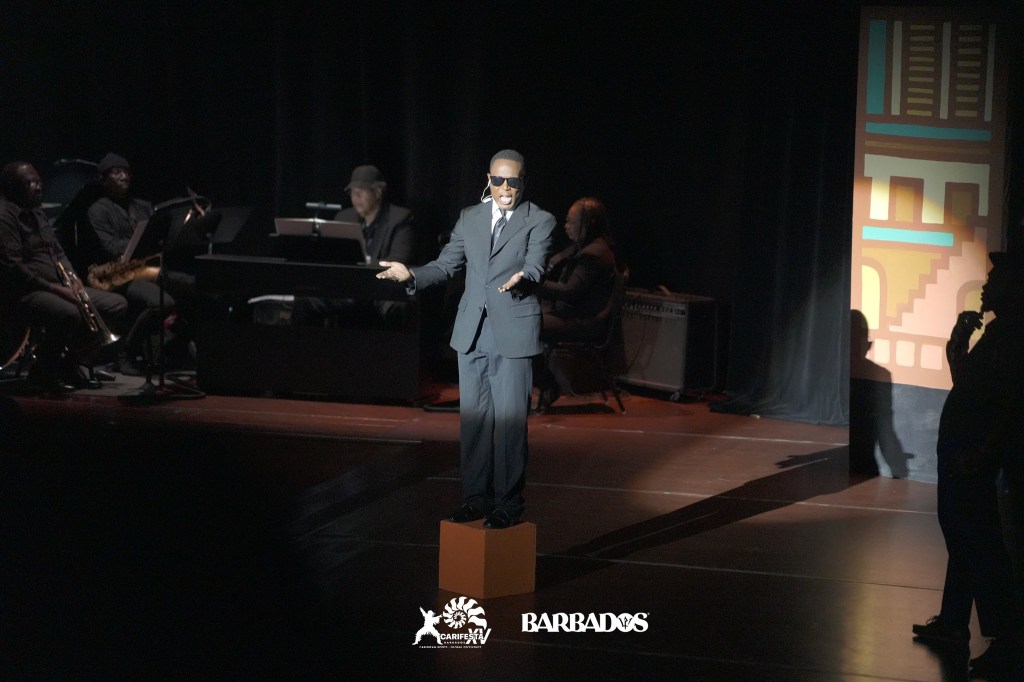

Undoubtedly, portraying an icon is no small task. Sparrow was a paradox: charismatic yet combative, witty yet profound, playful yet poignant. Roderick “Chuck” Gordon, himself a two time National Calypso Monarch, took on the role with conviction, and managed this balancing act with nuance. He avoided mimicry, instead channeling the essence of the eight time Calypso Monarch winner: the swagger, the sly grin, the quick wit, and above all, the sheer magnetism that made Sparrow, irresistible on stage. His performance of Jean and Dinah exemplified this as the audience roared. Staged against the backdrop of swaying backup singers, the calypso’s double edged humor landed with impact. Gordon’s Sparrow was both entertainer and agitator, a mirror of the Calypso King of the World himself.

But what is a King without the conquered, or a winner without stiff competition? Gordon’s performance was equally matched by the vivid portrayals of Sparrow’s peers, rivals, and the figures who surrounded him. Krisson Joseph’s ‘Melody’ served as a thoughtful counterpoint, his lyrical ease set against Sparrow’s youthful bravado, while Denzil Williams as Blakie/Kitchener grounded the stage with a weight that reminded us Sparrow’s dominance was hard won. What was particularly impressive was William’s effortless recreating Lord Kitchener’s signature dance and mannerisms, further concreting his characterization. Zachary Sosa’s ‘Johnny Wright’ captured the calculating opportunism of those eager to exploit calypsonians for profit, and Anton Brewster’s turn as the MC and /Delamonte (in addition to TT’s First Prime Minister) highlighted his versatility, moving fluidly between political gravitas and theatrical flair.

Photos courtesy: Nation News, Barbados

At the same time I was left to wonder, would being cast in so many key roles make it difficult for the audience to keep track? In my case, familiarity with the performers, and access to a program from a Trinidad staging earlier this year helped me navigate these shifts, but for those not familiar with the cast, the transition may not have been as seamless.

The female cast were equally commanding. Tants, brought to life by Aaliyah Johnson, radiated maternal authority and warmth, embodying the archetypal elder who guides, chastises, and protects with equal measure. In contrast, Harmony Farrell’s Jean Smith, the “high coloured” carnival queen, underscored how colourism shaped not only broader society but also the dynamics between women themselves. Their performances carried a believability that felt like a rebellion against the long-standing trope of women as passive subjects in calypso, instead asserting them as active agents in the cultural and social life of the time.

The Barbados staging added further richness with two Bajan actresses, whose presence deepened the work’s resonance. Hearing Sparrow’s Trinidadian story delivered in Barbadian cadence created a momentary dissonance that quickly transformed into something powerful. The native accents, set within their own land yet delivering a narrative born in another, underscored the very universality the production sought to affirm.

Editors Note: The Bajan actresses were Tiffani Williams and Toni McIntosh

Photos courtesy: Carifesta XV

It is worth noting that very little information about the production was available through the official Carifesta channels. Earlier stagings of Ten to One in Trinidad were accompanied by a detailed programme that listed cast members and offered valuable context, but this was absent in Barbados. Such a resource would have been especially useful here, given the doubling of roles, the introduction of new actors, and the need to provide the wider Caribbean audience with critical background. Beyond aiding clarity, it was also a missed opportunity to highlight the brilliant creative team and technical minds working behind the scenes.

Under Musical Director Marva Newton, the live band transformed the auditorium into a calypso tent. Positioned in plain view offstage right, the musicians were as much a part of the storytelling as the actors themselves, and served as the heartbeat of the production. Guitar, trumpet, saxophone, bass, and congas conversed with the singers, punctuating lines, amplifying emotions, and driving the narrative forward. The repertoire was immense: Carnival Boycott, PNM Victory, No Doctor No, Federation, Massa Day, and more – forty eight calypsos in total. Each reminded us that these works were never disposable tunes. They were barbed jokes, pointed sermons, protest anthems, and collective memories disguised in rhyme and rhythm. To hear them re-embodied at Carifesta was to witness how music rooted in one small island had blossomed into a shared Caribbean language.

This language was translated visually through Joanna Charles choreography, which ensured that the production was grounded in Caribbean movement, echoing the gestures and rhythms of the calypso greats while adding a physical language that amplified the storytelling on stage.

Yet if the production had a flaw, it was its density. With so many calypsos, historical references, and characters, newcomers to the form might have felt overwhelmed. The script, written some three decades ago, still bears the weight of its original framing. As a historical piece on one of Trinidad and Tobago’s most prominent cultural figures, the material is undeniably rich, but it does raise a pressing question: how does this story meet younger generations who may not know Sparrow or feel invested in his legacy?

The production, as staged, resonated deeply with an older crowd who lived through Sparrow’s reign or grew up in the wake of his dominance, but it risks leaving behind a broader audience whose connection to calypso is less direct. From my own experience, though I am familiar with Sparrow’s work and that of his more popular counterparts, not having lived through or close to his reign meant that I sometimes had to work actively to keep up in order not to lose the plot at times. The material, rich as it is, risks overwhelming those who lack that lived connection as its density demands a level of cultural recall that not every audience member may readily possess.

Now don’t get me wrong, the challenge is not in the material itself, but in how it is contextualised and delivered for today. Perhaps a reimagining of the marketing approach, highlighting Sparrow’s relevance to contemporary struggles, or drawing parallels between calypso and the popular forms younger audiences already embrace could bridge that gap. The brilliance of the work is undeniable, but without deliberate effort to translate its urgency for a new generation, it remains in danger of speaking mainly to those already converted.

The afternoon night closed with a rousing standing ovation. Among those on their feet was the Honourable Prime Minister of Barbados, Mia Mottley, whose presence underscored the significance of staging such a work at Carifesta. My experience at Ten to One was the embodiment of Carifesta’s purpose: to show that the Caribbean is a chorus, not a collection of solos. This presentation at a festival conceived as a regional celebration of art and a space to affirm cultural commonalities amid diversity, was ultimately an ideal choice. What Ten to One ultimately affirmed in Barbados is that calypso cannot be confined. It is not solely national, nor merely regional, but profoundly universal. Gibbons does not present Sparrow as a singer chasing fleeting acclaim, but as a visionary intent on widening his reach and reshaping the world through his music.

Though the material’s denseness and dynamism proved a challenge, by weaving bold directorial choice, effective characterization, and flawless musical direction, the play illuminateds calypso’s transformation from street-corner performance into a cultural force that gave voice to the silenced and reflected the ambitions of the overlooked. Gibbon’s Ten to One is a reminder that calypso is both a mirror of the past and a call to the present, insisting that Sparrow’s legacy and the art form he championed remain essential to how we see ourselves and how we imagine the Caribbean’s place in the world.

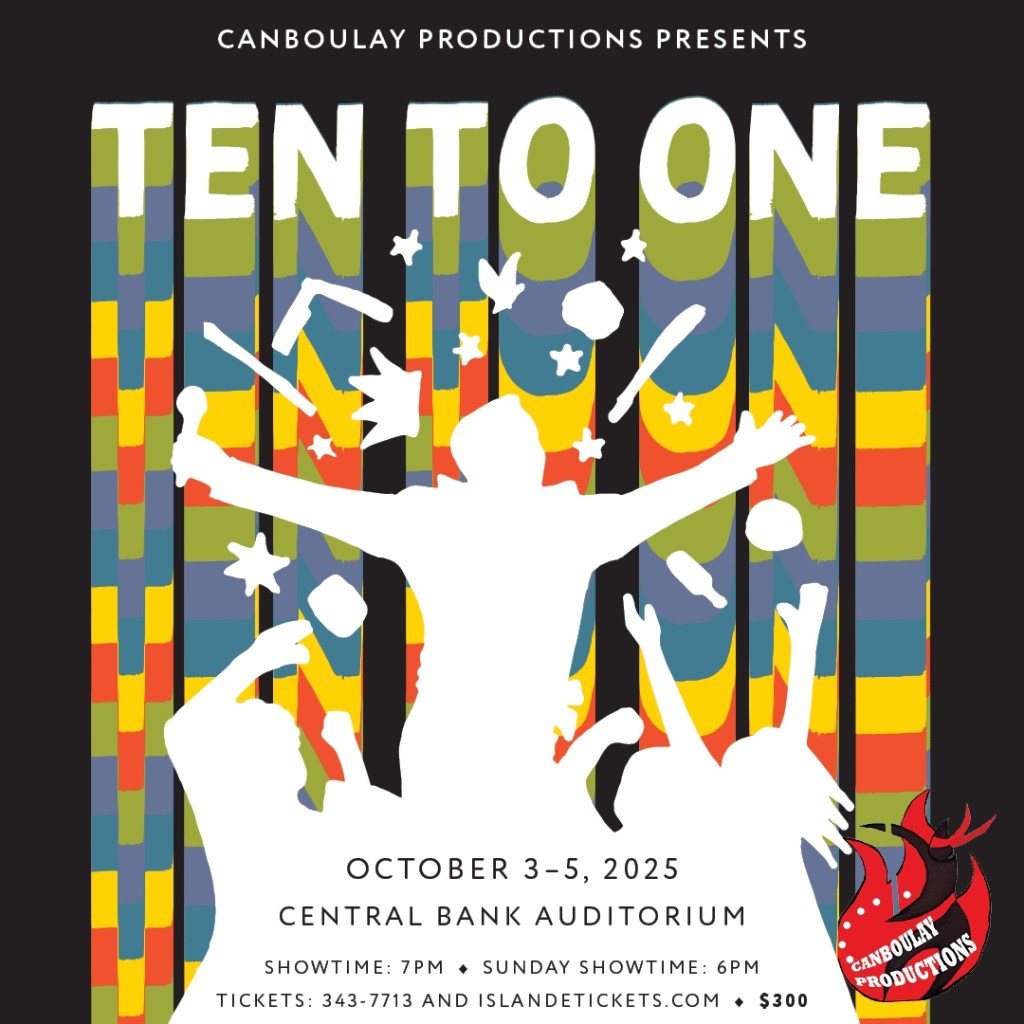

Canboulay Productions will be staging Ten To One again on October 3rd, 4th, and 5th, 2025 at the Central Bank Auditorium. For more information, visit them on Facebook and Instagram, or contact them at 868 343 7713, or on IslandETickets.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Hey there! I’m a cultural worker and creative strategist, blending storytelling, the performing arts, and digital magic to celebrate Caribbean identity. Whether I’m behind the scenes or in front of the screen, I’m all about keeping our stories bold, rooted, and real.

With a BA in Literature and Linguistics, I am the Public Relations Officer of The National Drama Association of Trinidad and Tobago, Editor-In-Chief of On Cue magazine, and a Casting Executive and Content Writer at the Trinidad and Tobago Performing Arts Network.